Kyoto Obubu Tea Farms

In January of 2025, Gentle Artefacts was joined by select collaborators for an ethnographic field excursion to Obubu Farms in Wazuka—to experience tea culture and agriculture through first hand encounters with the tea fields and the farmers who tend them. These materials are remnants of that encounter.

Farming in Wazuka, Uji, Kyoto

View of one of Obubu Farm’s mountainside tea fields

Nestled in a lush valley in the southeastern mountains of the Yamashiro region of Kyoto Prefecture, the town of Wazuka has remained a principal site of production for Uji teas for over 800 years—ever since the area was first selected for tea cultivation in the Kamakura period (1192-1333 AD). While contemporary Uji is a mid-sized city situated roughly between Kyoto and Nara, Uji tea designates teas yielded from the small farmlands and sloping fields scattered throughout the countryside that rises to the south and east of the Uji and Kizu rivers, respectively.

Historically, the genesis and gradual elaboration of Japanese tea culture—from the agronomy of its cultivation to the ceremony surrounding its consumption—is wholly imbricated with the evolution of the spiritual and political forces that structured everyday life across medieval and early-modern Japan. The most well-rehearsed of Japanese tea’s (possible) origin stories revolves around a Buddhist monk, Eisai, who in the final decade of the 12th century returned from an extended sojourn in (what was then Song dynasty) China with, among other things, two novelties that would significantly shape conditions of existence in Japan for the rest of the millennium: Rinzai Zen Buddhism and the saplings and seeds of Camellia sinensis, which is the Linnean designation for tea plants. Eisai, as the story goes, subsequently gifted seeds to Myoe Shonin, a distinguished monk from Kozanji Temple in Toganoo, Kyoto, in addition to detailed instructions concerning their cultivation, preparation, and storage: Eisai’s instructions were based on his own empirical observations of Chinese tea practices and documented over the course of his extended fieldwork in China (it appears that in addition to Buddhism and imperial court rule an inchoate anthropology was integral to the conditions governing Japanese tea’s emergence). Myoe in turn planted tea on the temple’s grounds and tended to them in what may have been Japan’s first tea garden. Later, he sent harvested seeds first to farmers in the Uji region and then to peasants farming lands throughout Japan’s farther reaching realms.

By the 13th century, tea was being incorporated into formal religious ceremonies, appearing both in Buddhist as well as Shinto rituals. Court nobles and other elites like the samurai developed their own semi-secular rituals for classifying and evaluating teas and tea producing areas, and in the 14th century, the Muromachi shogunate expressly encouraged the further development of tea cultivation in the areas surrounding Uji by investing extensive resources towards expanding the lands suitable for tea farming and towards deepening the agricultural and horticultural expertise of the craftspeople producing it. In the 14th century, Japan’s first tea shops began to appear in Kyoto, as a commercial class of merchants emerged in the imperial capital. Scholars like Sen no Rikyu, a 16th century Uji tea master and court advisor, elaborated the art of the tea ceremony—an admixture of buddhist spiritualism and an aristocratic manner predicated on patient pursuit of excellence in the practice and performance of cultural arts—which revolved in part around the intricate and highly embellished rituals for preparing, serving, and consuming matcha teas, which were also invented in Uji: the by-product of innovations alighted upon by Uji farmers experimentally tinkering with tea shading, harvesting, and processing methods.

The matcha powdered tea that is renowned today emerged in part through agricultural accidents. In the early 16th century, Uji area farmers pioneered methods for ‘shade-grown’ cultivation, in which the tender shoots of budding spring tea plants are covered to prevent exposure to direct sunlight for the period preceding their harvesting. Although the introduction in Uji of shade-cultivated tea cultivation techniques appears to to have been a pragmatic attempt to stave off early spring freezes of tea crops in this mountainous, high-altitude region, the effect on the tea when it was processed by grinding into matcha, was the enhanced umami profile and rich, deep green color that became and has remained characteristic of the finest matchas. More Japanese tea-defining technical innovation from Uji area producers followed soon after. Nagatani Sōen, an Uji tea farmer and producer from Ujitawara in the 1730’s initiated a novel refining method inspired by pan-fried roasting techniques indigenous to China. By lightly steaming the leaves just as soon as they are picked to arrest any oxidation, then cooling them before rolling each leave meticulously by hand to slowly dry it before heating it again to reduce excess moisture, highly fragrant, sweet, but delicately astringent sencha tea was born. Termed the ‘Uji Method,’ the technique took off widely throughout Japan, and the following century senchas became the most popular style of Japan tea for export—predominantly to the United States, the world’s greatest consumer market for Japan tea at the team—before becoming, in the 20th century, the most widely consumed tea domestically throughout Japan. Gyokuro teas, also known as ‘jade dew,’ were the product of ingenious hybridization of the ‘shade-grown’ covered cultivation technique pioneered for the production of the tencha that is ground into matcha, on one hand, and of the ‘Uji Method’ of steaming, cooling, hand-rolling, and reheating for producing senchas: gyokuro teas, with their delicate sweetness, balanced umami, and saturated green colored liquors came to eclipse even senchas in terms of relative quality rankings by tea experts and elite consumers alike.

Wazuka, the quiet farming village in a famed valley of tea

The town of Wazuka is a small place, but it has an outsized impact not only on the global reputation of Japanese tea but on the continuation of traditional craft practices for its cultivation as well. Prior to the development of highly industrialized tea agriculture, Uji teas drove Kyoto Prefecture to lead Japan in overall tea production in the latter 19th century. Today, Uji teas account for just 4% of Japan tea, and 45% of that yield is generated by the three hundred or so farming families still operating in Wazuka.

Towards the end of the Edo period, as Japan opened up for global trade, Uji teas producing areas were central for the export industry in teas that arose—particularly to the United States. Much of the land in and around present-day Wazuka town was cleared for tea cultivation in order to expand Uji tea area export volumes over the final decades of the 19th century. Then, as now, Wazuka is known for producing the most prized sencha teas in Japan. Wazuka farmers have seen the export market for its unique teas and matchas fall and rise and fall and rise again over the long 20th century since. And today, global and domestic tastes in tea are once again converging around the incomparable teas of Wazuka. But the traditional methods in tea cultivation and processing that have been sustained by independent producing families in and around Wazuka are under threat. Large scale farms and highly mechanized production methods are difficult for the small batch yields of hand picked and processed teas from Wazuka’s farmers to compete with. Indeed, multi-generation farmers have for a generation been retiring their fields. The traditions in tea craft and culture in Wazuka require innovation and adaptation if they are to thrive and survive in the centuries to come.

Enter Obubu Tea Farms…

View of one of Obubu Farm’s mountainside tea fields

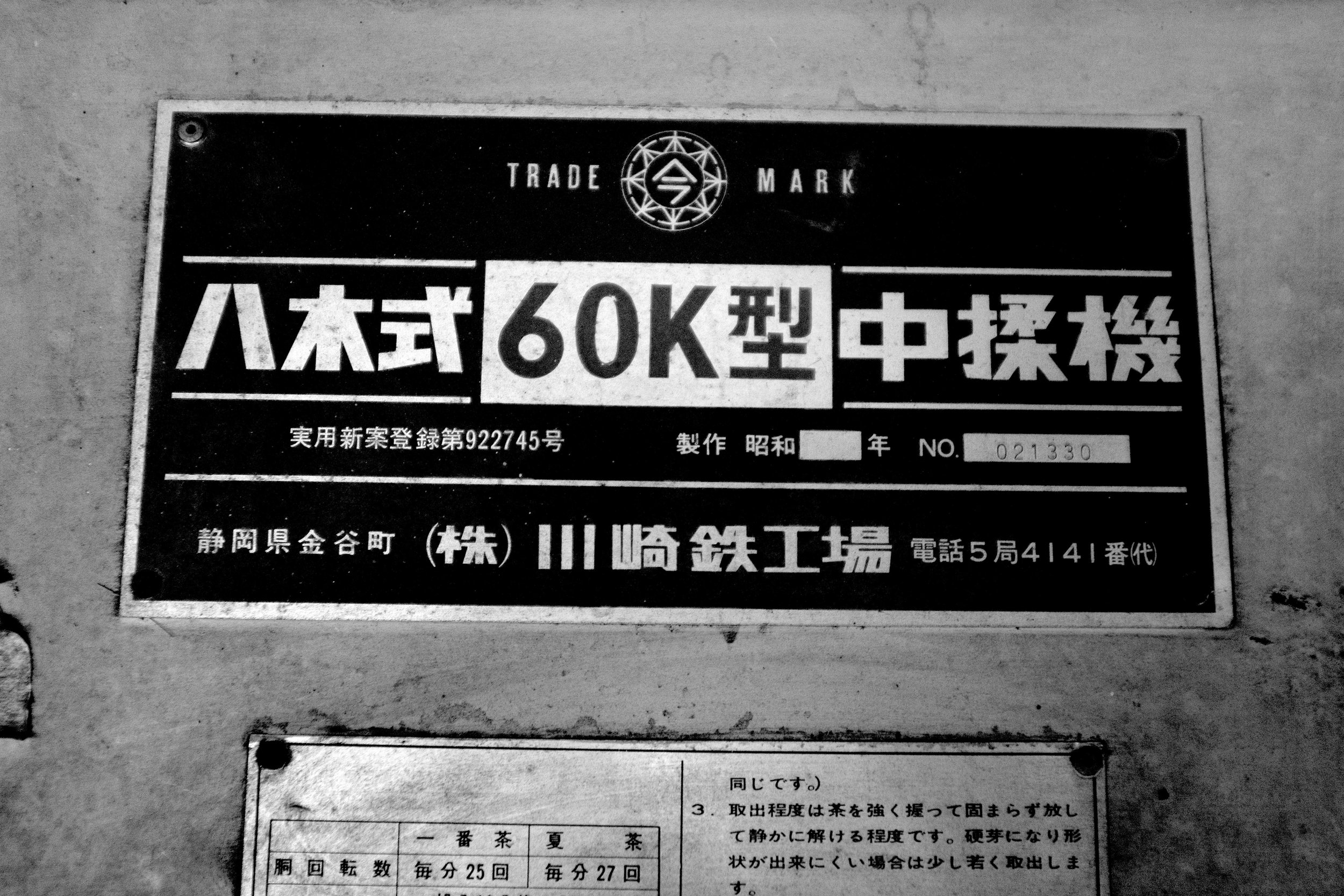

…Kyoto Obubu Tea Farms is a first generation family farm with a focus on sustaining and reinvigorating local traditions in tea cultivation, craft, and culture. With 4.1 acres spread across 14 fields, Obubu Tea Farms has for over fifteen years been widening its footprint in Wazuka, by acquiring the abandoned fields of retired farmers without farming heirs and restoring them to their full tea producing capacities. Harvesting is done by hand, and processing is performed on-site in the ‘processing factory,’ mostly with vintage machines acquired from locals who have upgraded to shinier more modern machinery. Their philosophy of tea and tea farming—like the spirit of tea culture proper to the Uji region itself—is one of continuous elaboration and reinvention, of honoring traditions by evolving them with care in the present, in order to meet the demands of the day. They strive to create teas that blend the old with the new, tradition with innovation, local Japanese heritage with global audiences and tastes. And they strive to continuously add to the legacy of technical innovation in agrarian arts and sciences that Uji tea production is historically so famous for. When it comes to Obubu’s mission with tea today, they have described their approach to Japanese tea craft as one of ‘new features, but the same face.”

Akky

“I want to make all the styles, like hard leaf and light steaming, a balance of umami taste and bitterness. Rare tea. Old tea. All the styles.”

Hiro

“We want to say to everyone, really say, that we are tea farmers: we plant, organize the tea field, harvest—we make everything from soil to your teacup. That is one of the important Obubu farm philosophy.”

Matsu

“Industrial tea production in Japan is a tour toefficiency. But here at Obubu, the way of thinking is artistic, produced by, and for, art.”

The Obubu Tea Farms Factory

Vintage tea steaming, heating, and drying machines in the Obubu Farm’s onsite treatment ‘factory’